Part 2 – Soil Residual Effects of Herbicides

By: Julianne Mason, Restoration Program Coordinator, Forest Preserve District of Will County

To preserve or restore native plant diversity and community integrity, it’s often necessary to apply herbicides to kill invasive plants. However, using herbicides can cause collateral damage to the native plant species that we’re trying to protect. In addition to direct collateral damage, I have begun to appreciate how the soil residual effect of herbicides can inhibit establishment of the native species that we’re trying to restore.

We spend a lot of money and crew-hours purchasing or collecting seeds of native plants to restore native plant diversity. However, I have seen many examples of where we have gotten almost no native plant establishment from these seedings. I started to consider the mechanism of how herbicide use to control invasive plants may be implicated in the lack of success of the seedings.

In a recent mesic prairie restoration project in northeastern Illinois, the PBP project area had been sprayed with Milestone herbicide (aminopyralid) to target Canada thistles (Cirsium arvense). Before I spent a hundred thousand dollars on native seed, I wanted to make sure that the residual herbicide level in the soil was low enough to allow the native seed to establish.

In another prairie restoration area in northeastern Illinois, we boom sprayed the MRP project area twice with Transline herbicide (clopyralid) to target teasel (Dipsacus laciniatus) and birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) before seeding a mesic prairie mix. I wanted to know why the seeding didn’t establish, and whether the residual herbicide level in the soil was low enough to try overseeding natives again.

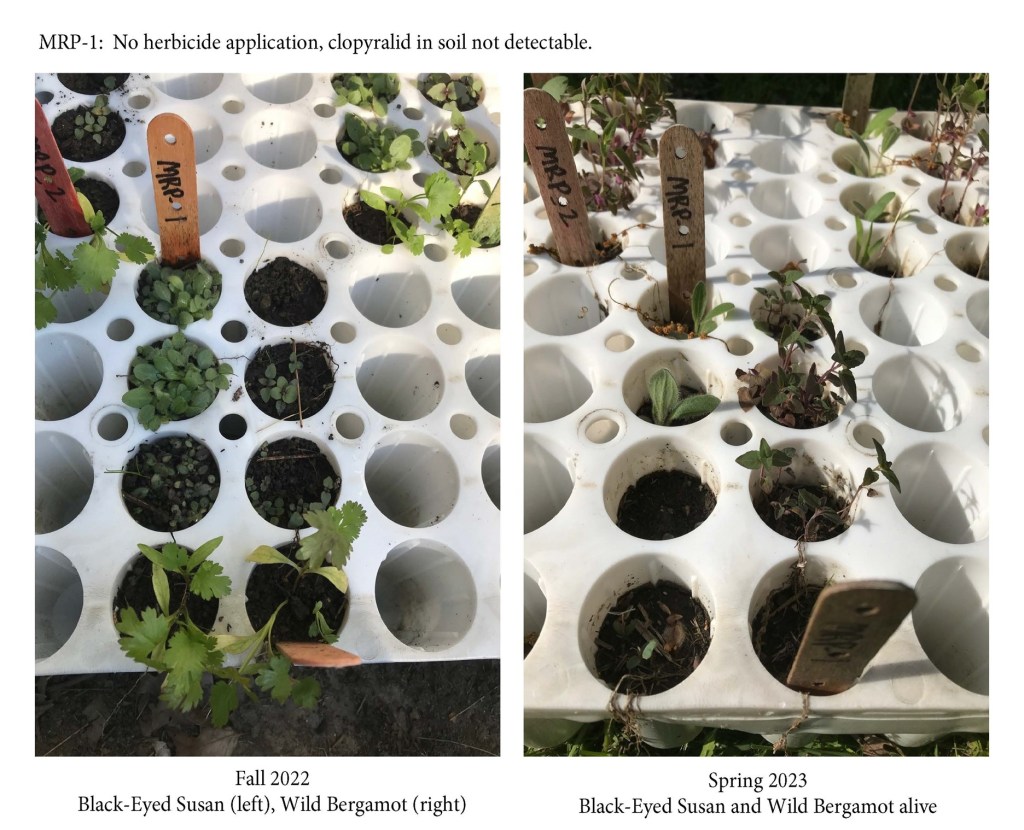

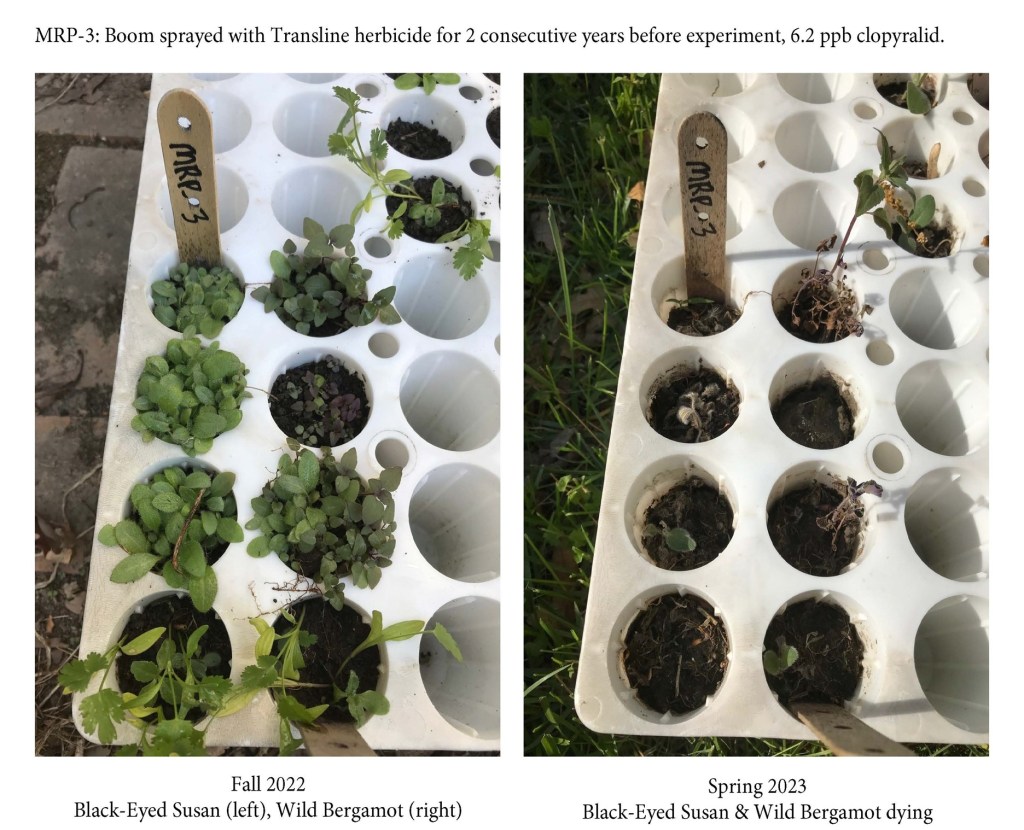

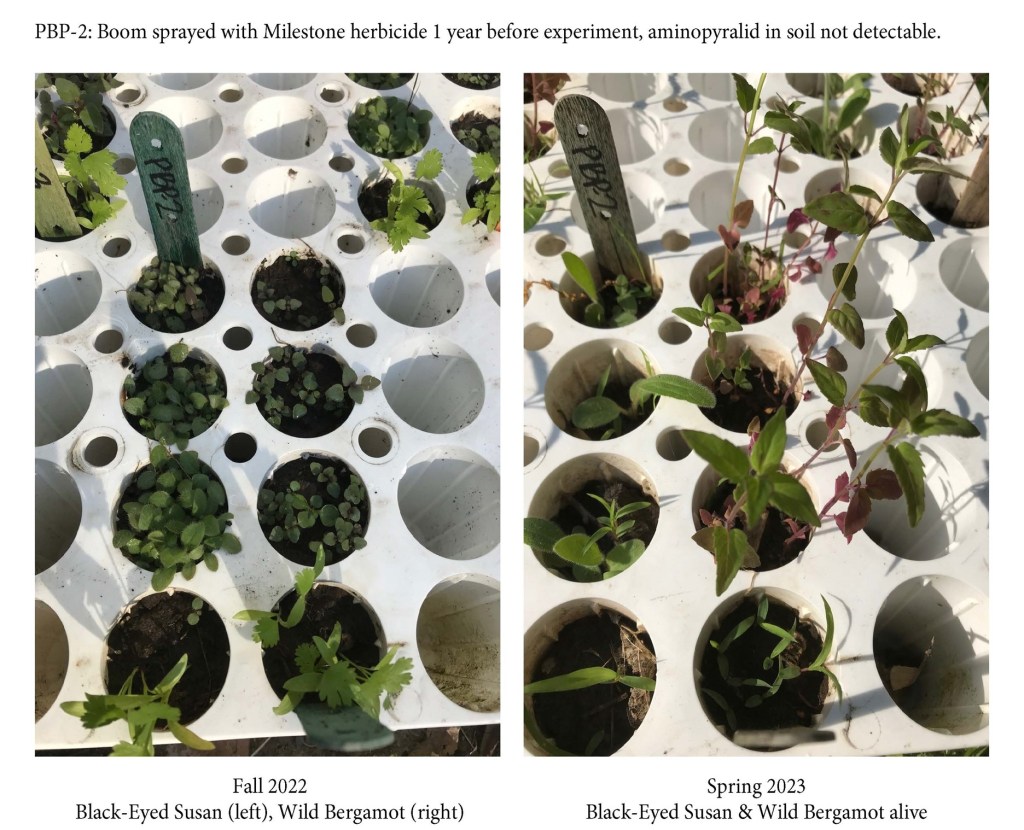

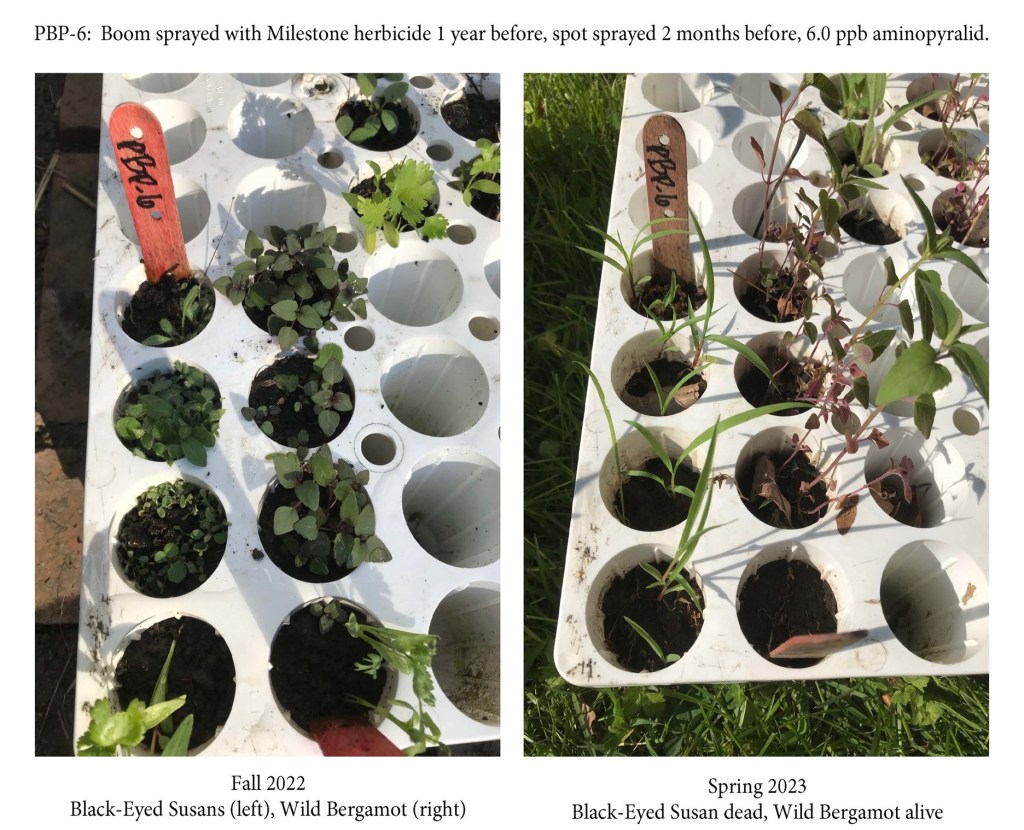

For both areas, I sent soil samples to the South Dakota Agricultural Laboratories for analysis during late August 2022. At the same time, I put soil samples from the two project areas in plug pots and seeded them with black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta; left plugs), wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa; right plugs), and cilantro (front two plugs). Black-eyed Susan is susceptible to both herbicides, wild bergamot is relatively tolerant of both herbicides, and cilantro is an annual that germinates readily (and I had extra seed lying around). In the fall of 2022, most seed had germinated of all species, and there was not any difference between the soil samples.

By the spring of 2023, there was a notable difference between seedling survivorship in the soil samples with higher levels of residual herbicide and those without detectable herbicides. In MRP-3, which had the highest level of clopyralid (from Transline herbicide) in the soil at 6 ppb, both the black-eyed Susan and wild bergamot seedlings were dying. In PBP-6, which had the highest level of aminopyralid (from Milestone herbicide) in the soil at 6 ppb, the black-eyed Susan seedlings were dead, but the wild bergamot seedlings were still alive. In nearly all the soil samples where the herbicide levels in the soil were below the laboratory’s detection limit, both black-eyed Susan and wild bergamot seedlings were alive.

Take-Home Messages:

- If you suspect that you might have too much herbicide residual in the soil, get it tested before spending a lot of time or money seeding natives!

- Be mindful of uncalibrated spraying – both uncalibrated boom spraying, broadcast spraying with a gun, and backpack spot spraying. Our two examples with the highest soil herbicide levels had received an uncalibrated spray (via backpack spot spray or uncalibrated boom).

- Be mindful of the accumulation based on consecutive years of spraying. Our two examples with the highest soil herbicide levels had also been sprayed two years in a row.

Here is a summary of the management history, the soil herbicide level, and the germination study results.

MRP-1: No recent herbicide activity.

Clopyralid level in soil: below detection limit.

Germination results: Establishment & survival of black-eyed Susans and wild bergamot.

MRP-2: Broadcast sprayed with Transline herbicide (0.5%; ave 12 fl oz/ac) 1 year before soil tests.

Clopyralid level in soil: 3 ppb

Germination result: Establishment & survival of black-eyed Susans and wild bergamot.

MRP-3: Broadcast sprayed with Transline herbicide (0.5%; 19 fl oz/ac) 2 years before soil tests.

Broadcast sprayed (uncalibrated) with Transline herbicide (0.5%; 40 fl oz/ac) 1 year before soil tests. *Note: this application exceeded the annual maximum application rate (24 fl oz/ac).

Clopyralid level in soil: 6 ppb

Germination result: Both black-eyed Susans and wild bergamot germinated but died the following spring.

PBP-1: No recent herbicide activity.

Aminopyralid level in soil: below detection limit.

Germination result: Establishment & survival of black-eyed Susans and wild bergamot.

PBP-2: Broadcast sprayed with Milestone herbicide (0.25%; ave 2.6 fl oz/ac) 1 year before soil tests.

Aminopyralid level in soil: below detection limit.

Germination result: Establishment & survival of black-eyed Susans and wild bergamot.

PBP-6: Broadcast sprayed with Milestone herbicide (0.25%; ave 2.6 fl oz/ac) 1 year before soil tests.

Then, spot sprayed teasel with Milestone herbicide (0.25%) 2 months before soil tests.

Aminopyralid level in soil: 6 ppb

Germination result: Black-eyed Susans germinated but died (only annual foxtail grass visible in 2023 photo). Wild bergamot established.

Conclusion: Remember, it’s not only Kill, Kill, Kill. In conjunction with killing invasive plant species, it’s equally as important to seed and promote establishment of a diverse native community. To allow native seed to establish, good practices are to avoid excessive spraying, be mindful of the soil residual effects of herbicides, and get the soil tested as necessary to know when it’s safe to apply the precious native seed. A finesse approach is much more effective than brute force in invasive plant management!

Thanks for the info, much appreciated.

Do you know the volume of herbicide per gallon of water for both backpack & boom spray applications?

The “Maximum Application Rate” on the label will state the yearly max amount of herbicide permissible. Milestone is 7 oz of product per acre per year. Spot spray of 14 oz/acre is permitted but only if you spray 50% of an acre. For Transline, it’s 2/3 pint per acre per annual growing season for California, but I assume everyone should follow that.

The Milestone label reports you can seed forbs 90 days after application, assuming the application was at the label rate. The Transline label has no such guidance. They want you to plant a test crop to assess herbicide injury before seeding desired plants into treated areas.

Whoops, I saw “uncalibrated” in your article & didn’t read further, not realizing only some of your applications were uncalibrated. My bad. I’m still having trouble understanding the application rates. For Transline, you say the annual max application rate is 24 oz/acre. I looked at a 2022 version of the Corteva label & the only max rate I can find is 2/3 pint (10.7 oz) per acre per year in California.

For spot spraying from a back pack, or even from a small tractor, stewards generally use a percent of the product, rather than a pints per acre measure. Like glyphosate might be applied at 1 to 3%, Garlon 3A at 2%, etc.. Sometimes those percentages are mentioned in the herbicide label. When percentages for a backpack are not noted in the label we ask other managers what they are using. The measure of pints per acre works for a big commercial grade tractor sprayer on flat open ground with a constant speed and easy maneuvering. With natural areas spot spraying the travel speeds are highly variable, trees are in the way, the fields are irregular shaped, the weeds are in patches, not over the entire field, etc..

I used backpack % volume for many years but not anymore. Here are the reasons I made the switch to volume per acre:

1) I grew uncomfortable with the variables affecting application rate, since my goal is to prevent off-target damage, to not waste money by using too much herbicide or have poor results with too little herbicide. Variables are operator spray technique, height of spray wand, sprayer pressure, nozzle type & nozzle wear over time. When I calibrate a backpack sprayer for a particular nozzle & technique, I have confidence I’m applying the right amount of herbicide. I admit not having data quantifying the impact of these variables.

2) For persistent herbicides like Transline & Milestone, as Julianne pointed out, it’s important to stay below the max annual rate, which is stated on the label as volume/acre. Even glyphosate & triclopyr products have annual max rates given as volume/acre. I don’t know why they specify it for non-persistent herbicides, but guesses that come to mind is exceeding the rate may cause off-target damage, negatively impact insects or increase soil mobility. We must do all we can to limit potential harm from our activities.

3) If others try to replicate my recommendations based on % volume, they may fail to achieve the same results if they use a different nozzle or have a different concept of the amount of vegetation wetting necessary.

4) As you say, only some labels state % volume. Garlon 4 is popular for herbaceous weed control & doesn’t state it. The label is a legal document so it should be followed, especially for those working on government owned or publically accessible sites.

5) Calibration is easy to do & needs to be validated only every few years.

Regarding patchy spray areas, when a backpack is calibrated in gallons per acre & you use that to calculate how much herbicide to use, you will be spraying patches at a rate equivalent to the one used for a large area broadcast boom sprayer regardless of patch size. I agree that using an atv sprayer for spot spraying or on uneven & obstacle laden ground is problematic due to varying vehicle speed.

Hi Don, I think I meant to use 1 1/3 pts per acre as the max amount of Transline concentrate that should be applied, which is actually 21 oz/acre (not 24). Typo, sorry!

Since the label doesn’t specify max annual rate (with exceptions for California & Christmas tree plantations), 1 1/3 pints seems reasonable since it is the max single application rate for labeled weed species. I’m going to use that max annual rate going forward-thanks for the guidance. Did you get that number from the manufacturer? It would be interesting to know what research the California max annual rate of 2/3 pints/acre is based on. However I found it appeared on the Transline label between 1995 & 1997 & in my experience, studies that old often aren’t up to today’s quality standards.

Thanks Julianne. Interesting information and helpful reminders. Much appreciated!

If youâre seeding farmland to prairie, it is also important to know the herbicide history. Many ag herbicides and especially more recently introduced residual herbicides have very long half-lives. Also, weather will play an important role. Many of these herbicides will break down faster and be leached out of germination zones (depending on K factor) in wetter years. With recent Midwest drought, likely a bigger problem.

[Image result for Polk County conservation logo]

Doug Sheeley

Natural Resources Manager

11204 NE 118th Avenue; Maxwell, IA 50161

P 515.323.5395 | C 515.490.5152

leadingyououtdoors.orghttps://www.polkcountyiowa.gov/conservation | jesterparknaturecenter.comhttp://www.jesterparknaturecenter.com/ | dsmskatepark.comhttp://dsmskatepark.com/

Connect with Us on: [cid:image003.png@01DAB75F.42935960] https://www.facebook.com/PolkCountyConservation/ [cid:image004.png@01DAB75F.42935960] https://twitter.com/PolkCCB [cid:image005.png@01DAB75F.42935960] https://www.pinterest.com/polkccb/boards/ [cid:image006.png@01DAB75F.42935960] https://www.instagram.com/polkcountyconservation/ [cid:image007.png@01DAB75F.42935960] http://leadingyououtdoors.blogspot.com/ [cid:image008.png@01DAB75F.42935960] https://www.youtube.com/user/PolkCoConservation