By Don Osmund, volunteer steward

The tool of choice for this is a brush saw. But some projects may benefit by adding an articulating hedge trimmer, where the blade assembly angle is adjustable so it can cut parallel to the ground while the operator stands upright. I often work alone on a large site & I wanted to make better time by cutting a wider swath. Also, I work on steep rocky slopes & I have a fear (perhaps baseless) of stumbling & somehow making contact with a brush saw blade.

The discussion forum at http://www.lawnsite.com was particularly helpful in selecting a brand/model along with usage & maintenance tips. Battery technology has improved to the point that I didn’t have to buy a gas powered model. I don’t have a pickup truck or outdoor shed, so storing & transporting gas is a safety issue, plus gas tools are noisy & smelly. Several brands would be good choices, but I selected Stihl because there were plenty of professional users on the forum & a nearby power center sells & services them. I chose the HLA-66 because compared to other models, it weighed less, was less expensive & fit my use case of semi-professional reliability. Multiple people on the forum commented that this model held up well during commercial use, but probably wouldn’t take abuse as well as the more expensive models. It has two 20” long double sided blades, so it cuts on both the backward & forward strokes. The blades can fold up against the shaft for transport. For a mix of light density vegetation/high on-time & high density/low on-time I get 3.5 hours use on an AP300S battery. So with 2 batteries I can cut all day.

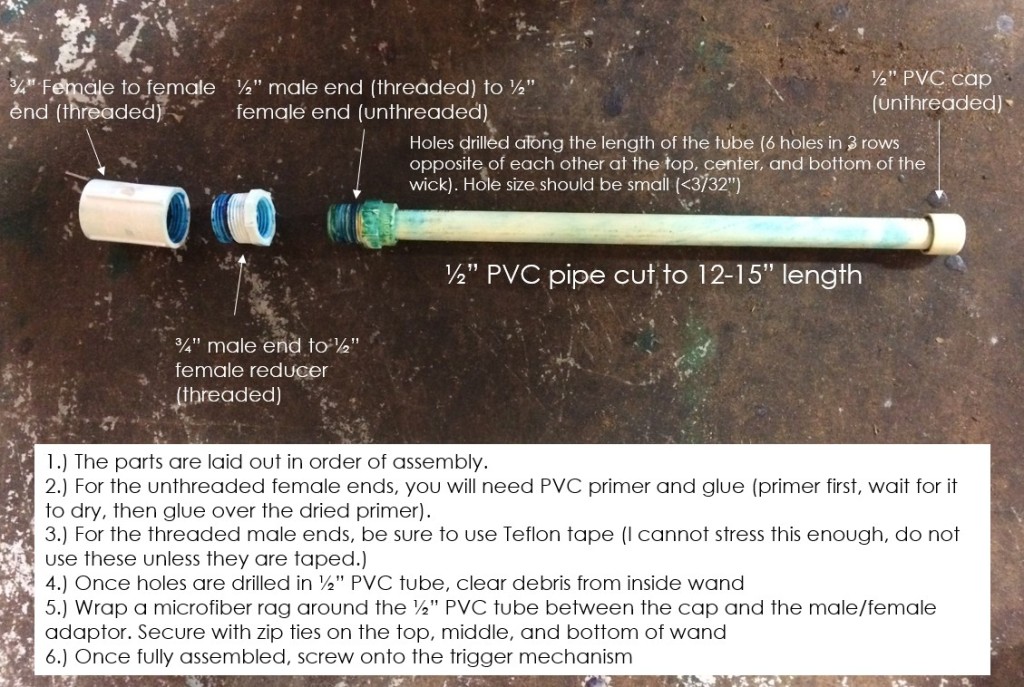

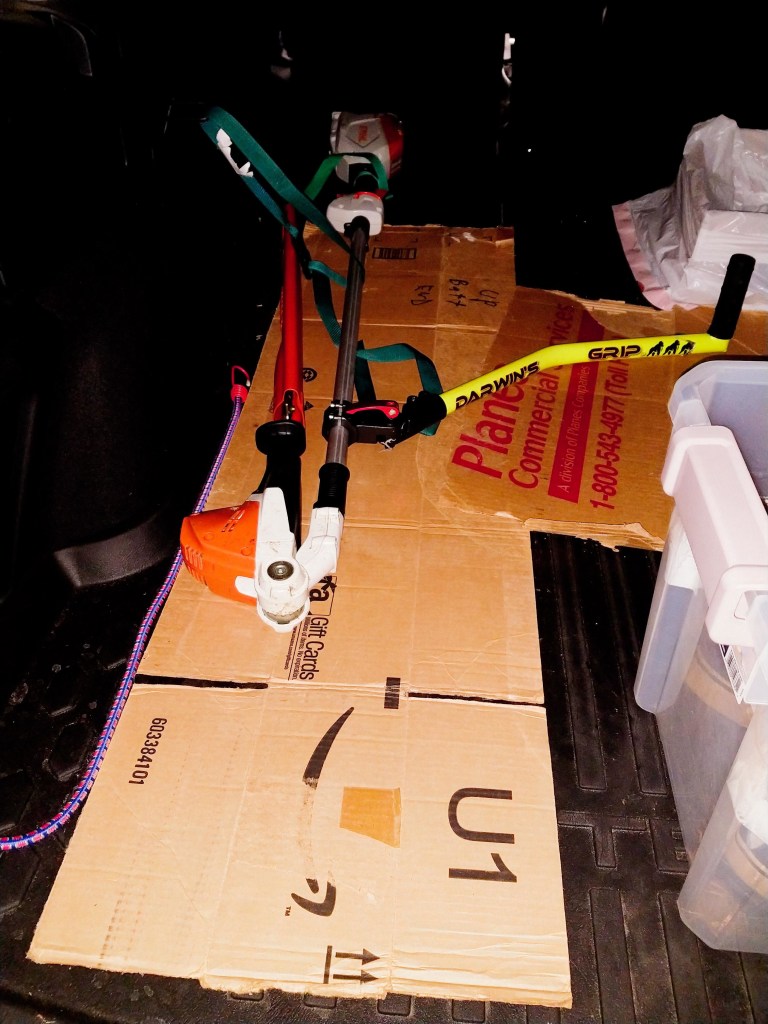

Above: The trimmer in transport mode (55” length). Blade protector is in place, tool is secured to the car in 2 places with straps & battery is removed for safety. Cardboard is in case the trimmer contacted poison ivy, wild parsnip or knapweed. The Darwin’s Grip can be folded closer to the trimmer shaft, but I decided not to test the quality of the quick release lever.

The first challenge was how to avoid abusing my body during long periods of use. When cutting ground level vegetation, the tool is fairly heavy & I found myself stooping over too much, which is hard on my back. A special handle called a Darwin’s Grip (the yellow attachment in the photo) was necessary because it provides a lifting point near the bottom of the shaft to support the weight of the motor & blades. It’s a replacement for the D handle that comes with the tool & is adjusted as follows. The clamp position on the tool shaft is chosen so the blades are the proper distance from ground when your arm is straight. The clamp angle on the shaft is chosen so that your wrist isn’t bent unnaturally when the tool is on either side of your body. The angle between the tool shaft & Darwin handle can be easily changed with a quick release lever. I adjusted it for good leverage when lifting the tool while not applying too much pressure on my hands. It can take several weeks to dial in the settings for an individual operator, which may be a problem if the trimmer is used by multiple people. After adjustment, the arm you use for the Darwin will be straight, the blades will naturally hang parallel to the ground at the desired height, & it will be easy to lift the tool up and over vegetation. Also necessary to support the top of the shaft (where the battery is) is a shoulder strap that comes with the trimmer. At first this seemed inadequate, so I tried a cheap harness that distributes the weight on both shoulders, but it didn’t allow me to switch the tool to the other side of my body & didn’t hold the tool low enough. Perhaps the more expensive harnesses from Stihl, Makita or Husqvarna would work better. Now that I’ve used the single shoulder strap all summer, I like it. It’s simple, allows me the relief of putting the trimmer on either side of my body & supports the weight well.

The main caveat with this tool is the wide swath means it has to fight through a lot more vegetation than a brush saw, & battery power instead of gas is a further limitation. It’s great for small diameter brush, wild parsnip, goldenrod, thistle or sweet clover if the grass density is light. It’s also good for cutting warm season grasses up high (where stem density is low) to prevent seed set. In low density vegetation with no rocks, cut height is 2-3”. For high density clover patches it tends to be 4-6”, which may be too high if the lower stem buds survived the shade created by the patch & resprout. Next year I’ll work on my technique to get lower. Some weeds need to be cut close to the ground to minimize reflowering & they are sometimes embedded in dense grass. The tool will still work in that situation, but you have to slow down to the point that a brush saw might be just as fast or faster. Plus dense vegetation will shorten the battery run time. In dense vegetation, I found it’s better to cut half the blade width at a time & instead of sweeping the tool in an arc, angle the blade into the uncut weeds & drag it backwards. Perhaps a gas powered model would work better in grass.

After every use, spray both sides of the blades with Fluid Film, which lubricates, prevents sap buildup & doesn’t harm plants. If you have patience, blades can be sharpened using a hand file without disassembly. Grinding wheels are faster but remove too much material, so use a narrow belt sander or sandpaper discs. Disassembly takes skill as you have to torque the bolts just right or vibration will loosen them, or the blades/motor can overheat if they are too tight. If you pay to have it done (about $30), choose a power center that has experience on these tools. A sharp blade will increase tool life. The gearbox is easy to clean out & lube with Stihl Superlub FS. Incompatible greases can cause a sticky disaster, so clean out the old grease if you intend to try a different type.

I like this trimmer because it’s a good match for my situation, where I need to cut scattered patches of weeds over a large area while working alone. Brush saws (or in some cases, perhaps a gas powered hedge trimmer) are a better choice for large areas of weeds in dense grass, large diameter brush, sites where resources are available for multiple brush saw operators or when cutting warm season grasses low to the ground in order to increase sunlight to seeded forbs.