By Becky Collings, Karen Glennemeier, Justin Pepper, and Daniel Suarez

At the upcoming GRN meeting in Barrington, IL, we will visit a number of local restoration sites, including Galloping Hill in NW Cook County.The focus of this field tour will be our Qualitative Rapid Assessment, described below, but we also wanted to share an overview of the site including the restoration goals and progress and an overview of its management history.

For those that just want the high-level summary of the site, this place is special because it:

- Was a first, grassland bird scale, multi-partner restoration aiming for prairie birds in a rich native natural community at the 4000-acre Spring Creek Forest Preserve

- Had a strong early grassland bird response, largely sustained for ~17 years

- Is becoming a high-quality, dry-mesic prairie restoration with hand collected, local ecotype seed, largely through volunteer stewardship, now expanding from ~20 acres to 60 acres and including wetter habitats surrounding the hill itself.

Management History

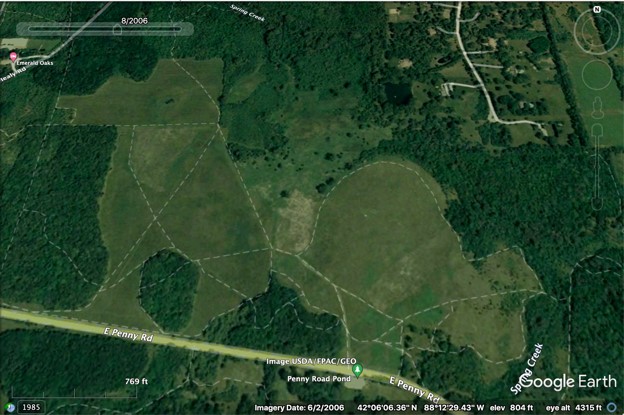

In 2005, Audubon, in partnership with the landowner, the Forest Preserves of Cook County as well as Citizens for Conservation, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the then nascent Spring Creek Stewards volunteer group, launched the restoration of Galloping Hill. The initial size of the grassland restoration project was 110 acres at the heart of the nearly 4,000-acre preserve.

Given the scale of the area, habitat restoration at Spring Creek allowed for grassland restorations large enough to be significant for ground-nesting grassland birds. Whereas previous restoration work at Spring Creek had focused on a small remnant prairie, this project was designed specifically with the suite of grassland obligate birds in mind.

A project was designed to reduce fragmentation of the grasslands in the immediate term and to begin restoring healthy prairie habitats in the years ahead.

Initial brush mowing and the removal of trees that had fragmented the grassland occurred over the winters of 2005 and 2006. Bird results were immediate and dramatic, 950% increase of Bobolinks, 650% increase for Meadowlarks in the years immediately following the clearing work. With those encouraging early results, the Spring Creek Stewards, the site’s new volunteer stewardship group, began the decades long project of restoring a diverse prairie. We wanted grassland birds, but in a healthy, native natural community.

Galloping Hill has remained a top priority for seeding within the Spring Creek preserves, even as the Stewards started new restorations (currently managing about 300 acres). Donated by Citizens for Conservation, seed amounts and mixes varied from year to year but were always interseeded into non-native cool season grasses at a very light seeding rate, perhaps averaging 4 lbs per acre. Seeding has been augmented by a few plug plantings through the years, primarily spring ephemerals like prairie violet, violet wood sorrel, Seneca snakeroot, prairie phlox and bastard toadflax. Native cool season grasses including porcupine grass and Lieberg’s and Scribner’s panic grass have also been reestablished.

The focus of the seeding started high and slowly worked down the hill, especially once the drain tiles at this site were mapped and valved in 2011.

Wetland/ Sedge Restoration—Following the 10 Warriors approach, wetland restoration began in earnest in 2018. Since then, more than 10,000 sedge plugs have been planted and reed canary grass has been pursued and treated with grass-specific herbicide.

Hay Meadow Expansion—in 2020, a 20-acre expansion was initiated in a hay meadow just NW of Galloping Hill which combines with a more recent expansion to the SE to now have about 60 acres under active restoration, not just grassland management.

Since the initial mechanical work, 90+% of the work has been done by volunteers with support from Conservation Corps, FPCC staff, and occasionally, contractors. The Forest Preserve District has prioritized burning at this site which has been critical to the progress to date. The site has been burned annually since 2005 (16 burns between 2005-2021). Most burns have occurred in the spring with the exception of fall 2009, 2020, and 2021.

How are we doing, and what do we do next?

(a.k.a. Monitoring & Adaptive Management)

Plants – Quantitative Monitoring

Vegetation transects were established early in the restoration and have shown steadily increasing floristic quality, approaching that of our region’s highest quality prairies after just fifteen years of management.

The speed and success of the restoration are due to the steady commitment of volunteer stewards, combined with a strong partnership among volunteers, land agencies, conservation non-profits, and contractors. Galloping Hill also has benefited from the experience of earlier restorations including Somme Prairie Grove, Nachusa Grasslands, and Grigsby Prairie.

Plants and overall community – Qualitative Assessment

We have introduced a new approach to adaptive management that we call the Qualitative Rapid Assessment (QRA). We’ll be sharing this process at our Galloping Hill tour during the conference – here’s the basic idea. A small group visits an area and begins with 10 minutes of each person individually observing the presence of invasive, conservative and matrix species, as well as the overall diversity and the sense of subjective quality or degradation. Each person assigns a score based on a simple, defined scale. Then the group convenes and discusses, reaching consensus on a score, but more importantly filling in the reasoning behind that score and, critically, determining what happens next. What’s missing, and how do we bring it back? How is this restoration most likely to go wrong? What’s the management history, does it explain what we’re seeing, do we think our approach needs tweaking? How, if so?

We’ve found that this method produces scores that align with quantitative floristic quality metrics. It deepens participants’ understanding of an area’s condition and management needs. It provides an actionable management to-do list. And it’s a meaningful, enjoyable exercise for both beginners and experienced restorationists.

Birds

The initial response from the brush clearing was heartening (see Figure 5 below) and while the numbers for individual species have bounced around a bit, Galloping Hill has consistently hosted strong breeding populations of Henslow’s sparrows (14 in 2020) and Bobolinks (34 in 2020).

Monitoring has continued since the project started, but since it has occurred under different protocols, we are not presenting an unbroken sequence of results.

Eastern Meadowlarks, Savannah and Grasshopper Sparrows have declined from high counts in the first 5 years of the project. These three species have also shown significant population declines regionally, as recently reported by the Bird Conservation Network so it is unclear how much of this decline is a local versus regional issue.

Grasshopper Sparrows would benefit grazing or other means to return to early successional habitat, but 2022 was the year of the Grasshopper Sparrow as they were found in multiple places within Spring Creek where they had been absent for years, this includes at least 4 at Galloping Hill.

The decline of Savannah Sparrows and Meadowlarks is a bit more of a puzzle and we welcome thoughts from others on this.

Addendum: The Qualitative Rapid Assessment is available here: https://tnc.box.com/s/t1amflh005fs30yywx2ac65e6l2q9bew

The qualitative rapid assessment method sounds very useful, looking forward to further updates/details – will these be posted online?

Caleb, I just updated the blog and included a link that hopefully works to the Quality Rapid Assessment. https://tnc.box.com/s/t1amflh005fs30yywx2ac65e6l2q9bew

When is the meeting? Might want to attend as an observer and draw lessons for local projects (south central Illinois). Henry Eilers

Sent from my iPhone

>

August 16 and 17, 2022

Savannah sparrows really like old fields – maybe that’s part of the answer. Also, bobolink and savannah sparrow are two birds predicted by Audubon to be moving out of the region due to climate change. Could we be seeing that?

Curious as to what your basis is for saying that “ Volunteer bird monitors from the Bird Conservation Network were reporting plummeting populations of Bobolinks, Meadowlarks, Grasshopper and Savannah sparrows.” When the restoration began, the site was too fragmented for any of those species. The discovery of about a dozen HESP in those fragmented fields brought this area to our attention.

Thanks for the careful reading, Judy, and please correct the record if you feel that is misstated.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that those species were just hanging on and about to blink out from the site? Or “had plummeted” rather that “were plummeting?”

The focus on grassland birds was less because of local declines and more because they were the fastest declining group in the nation so we wanted to create more habitat for them – especially by removing fragmentation, which this was a perfect site for. Maybe “National bird monitoring over the past decades was reporting plummeting populations of Bobolinks, Meadowlarks, Grasshopper and Savannah sparrows. So, a project was designed to reduce fragmentation of the grasslands in the immediate term and to begin restoring healthy prairie habitats in the years ahead.”