Katharine Hogan, PhD, Director of Conservation

Lauritzen Gardens, Nebraska

In 2016 I came to Nebraska for what I thought was going to be a one year sojourn in TNC Nebraska’s Hubbard Fellowship program. Now it’s 2025, and I’m still here, likely to stay! I got so hooked on prairies that I started leading the conservation department at Lauritzen Gardens in late 2024, with a focus on imperiled plants of the Great Plains and Midwest.

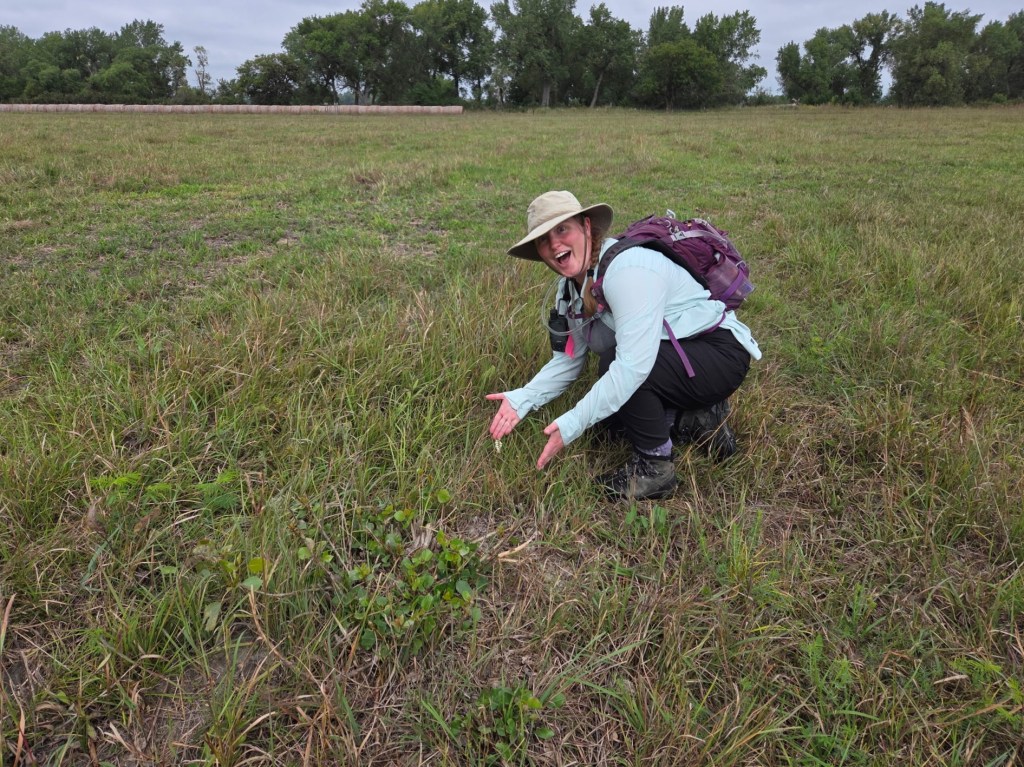

A photo of Katharine, who is very excited to have found her first Spiranthes orchid ever – in a hayed and grazed prairie restoration, too! Visual signs (plus the wonderful smell) suggest it’s S. magnicamporum, we are hoping to do genetic sequencing to confirm.

Pivoting from habitat conservation to species conservation is making me see opportunities everywhere for these two branches of conservation to join forces and accomplish more together. Botanical gardens do great focused conservation work, but I think we’re ideally situated to do more, and bridge the worlds of plant conservation research and plant conservation in practice. To illustrate, I’ll briefly describe a project we started this year and how we hope to scale up from lab-based conservation methods to more at-scale restoration and management of imperiled species.

Woolly milkweed

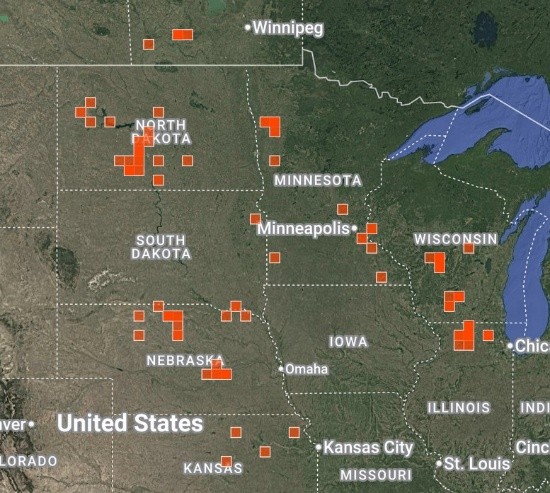

Some of you may know the woolly milkweed (Asclepias lanuginosa), but most folks I talk to haven’t heard of it – I hadn’t either until I joined Lauritzen! It’s small and unobtrusive, and most sightings are widely scattered individuals. More critically from a conservation standpoint, most records say it rarely flowers or sets seed. I’ve only found a couple papers in the scientific literature about it, which suggest the species is highly clonal (potentially a sign of low genetic diversity), and is difficult to obtain seeds for. In Nebraska, it’s our earliest flowering milkweed (sometimes late April!), and consensus is that it’s declining across much of its range (see screenshot).

A screenshot of documented woolly milkweed occurrences on iNaturalist. Retrieved 11/14/25.

Woolly milkweed flowering at Gjerloff Prairie, Hamilton Co., Nebraska. Photo courtesy of Prairie Plains Resource Institute/Sarah Bailey (2025).

We chose to begin conservation work on the woolly milkweed as it’s considered globally vulnerable (G3, NatureServe 2025), little is known about it in Nebraska, and Asclepias species are charismatic thanks to their association with monarchs. There is a little overlap between the earliest spring migrating monarchs and Nebraska woolly milkweed blooms. It’s also possible that monarchs lay eggs on plants that have already bloomed, but we don’t know yet. If anyone has insight on this, please reach out!

Among other locations, we’re working with Prairie Plains Resource Institute to conserve a population of woolly milkweed at Gjerloff Prairie (loess hills remnant) hear Aurora, Nebraska. This year we tackled two objectives: setting up a long term monitoring study, and attempting an embryo rescue protocol if there were any seeds (more details on that below). We surveyed four known colonies at Gjerloff, which totaled 165 stems. The average flowering rate was 18%. Only one seed pod matured; a few others started to form then aborted.

Plant #118 (left), the one individual that successfully produced a pod in 2025. Plant #117 (right) started to form a pod but it was either aborted or eaten by a “helpful” critter. Photos courtesy of Prairie Plains Resource Institute/Sarah Bailey (2025).

In additional to annually counting all plants and blooms, we marked 39 plants with metal aluminum tags to track more in-depth over time, allowing us to calculate population demographics, growth, and any responses to management. To me, this was a critical first step – population surveys of imperiled plants are common, but I rarely see them focus on management, which has implications for our ability to steward these plants in the long term. Not only that, it can take years to understand complex processes like fire and grazing.

Katharine rolling up the transect tape after tagging woolly milkweed plants for long-term study (right), and plant #118 with immature pod forming. Photo on left courtesy of Allison Butterfield (2025).

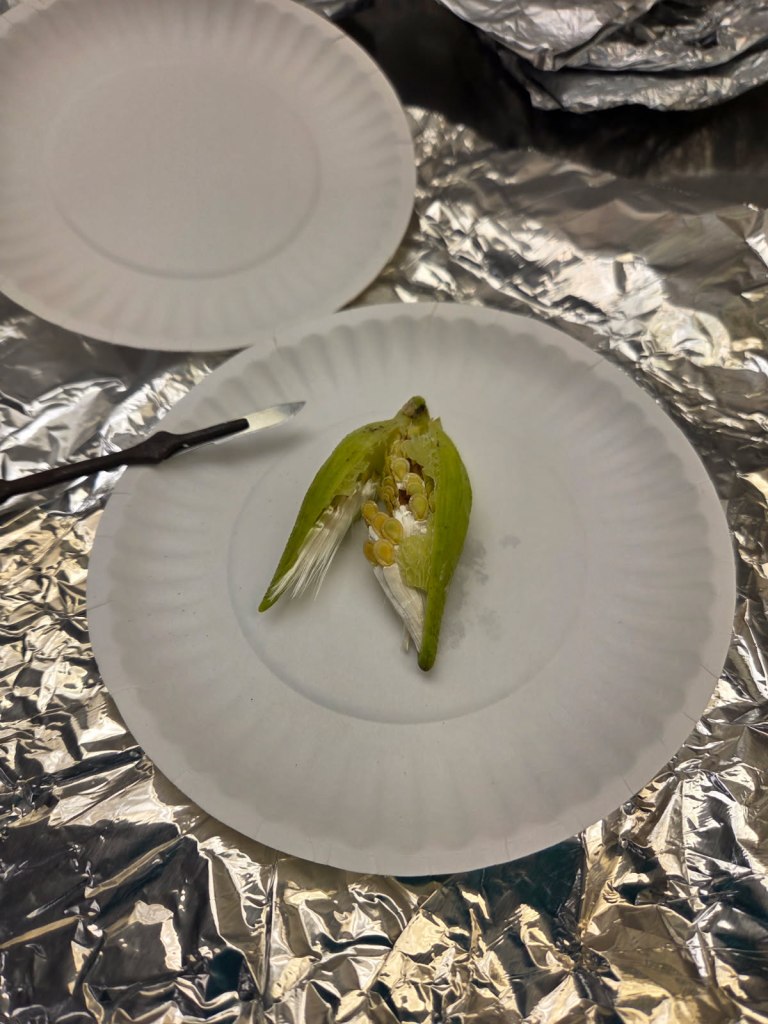

The one seed pod from plant #118 was harvested in the second week of July and brought back to Lauritzen for an embryo rescue attempt. No seeds from a pod produced by this population a few years ago germinated via typical Asclepias propagation procedures, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they are completely inviable. Sometimes the embryos are capable of growth but are not vigorous enough to break the seed coat. Removing the embryos and placing them into a sterile (in vitro) environment on a nutrient-rich growing media has yielded higher germination and growth rates in other milkweed species, so we decided to try it. One paper also found harvesting the seeds earlier than normal (before the pod splits) improved germination with the embryo rescue method.

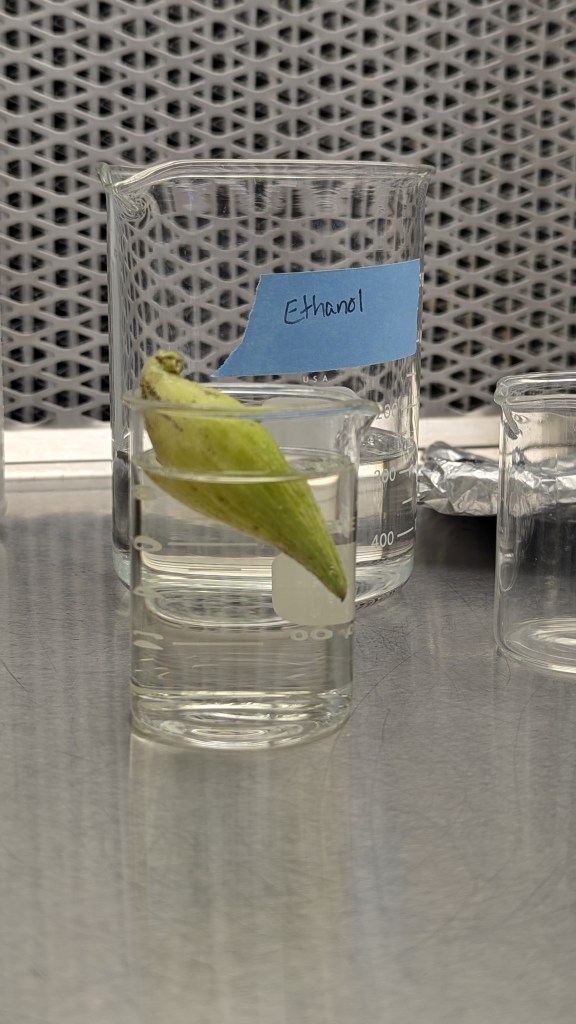

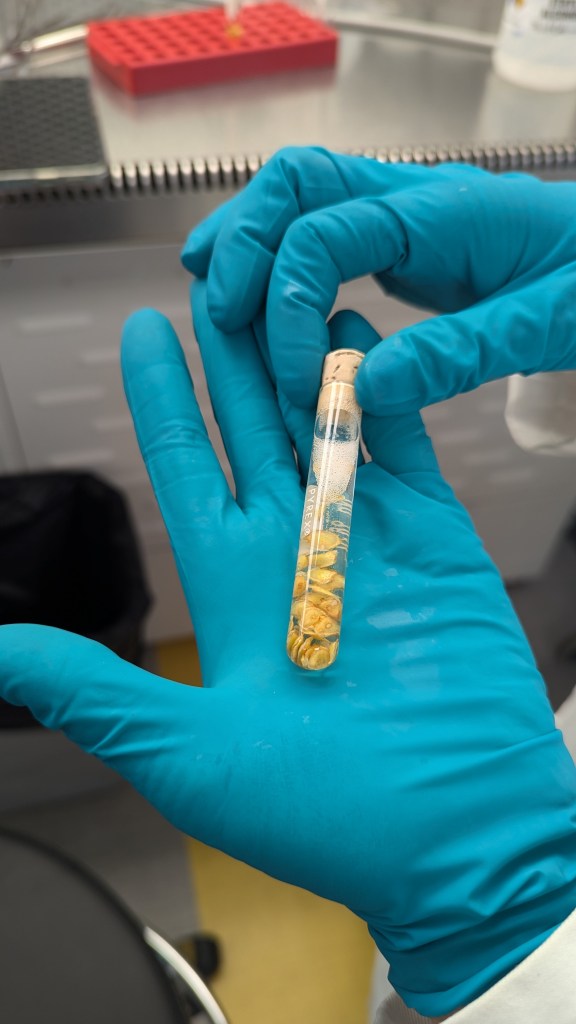

The seed pod contained 54 pale but fully formed seeds, and 11 underdeveloped seeds. We sterilized the outside of the pod with ethanol, then sterilized the seeds themselves to reduce any chances of contamination in the sugar-rich growing media.

Sterilizing the seeds from #118’s pod. We were so afraid the pod was going to have nothing in it!

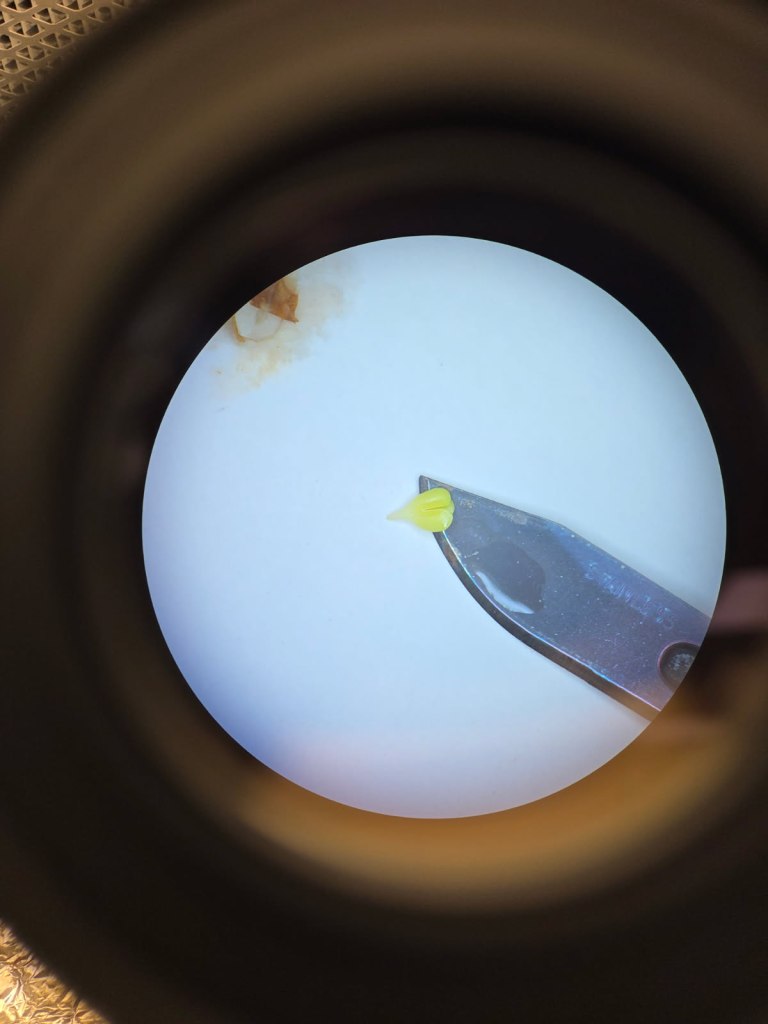

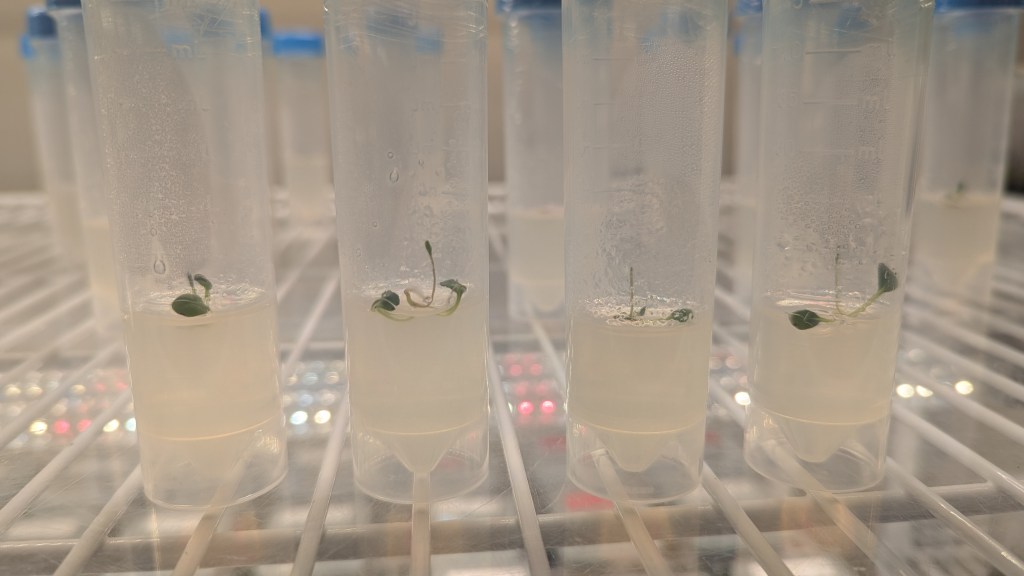

Without going too much into the remaining details, we carefully excised the embryos from the seeds under dissection scopes and placed them on the growing media into individual test tubes to eliminate potential cross contamination. The tubes were then places under grow lights in our tissue culture room, and we impatiently waited to see if they would grow. We also did the embryo rescue on a dozen butterfly milkweed (A. tuberosa) seeds from around the gardens, as a comparison.

Embryo excised from a seed under dissecting scope (left); test tubes with excised embryos in climate-controlled tissue culture room (right).

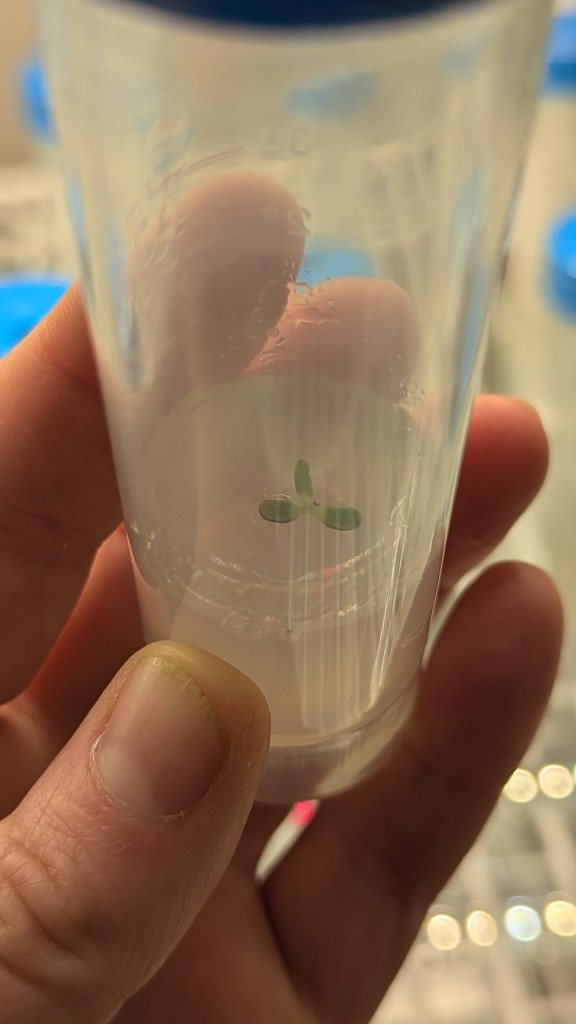

Woolly milkweed embryos forming cotyledons and initial shoots.

We soon transferred the embryos to new media, and gave half some hormones to stimulate root and shoot production as some seemed to be having difficulty getting started. Fun fact, the hormone is actually the herbicide 2,4-D, just in miniscule amounts instead of the larger dose that forces plants to grow too fast to sustain.

Within about 8 weeks, most shoots had turned into what could only be called little frankenplants. They produced clusters of very thin, weak shoots instead of a single stout shoot like the butterfly weed seeds did. We think this is either 1) a reaction to the 2,4-D or 2) some indication of lack of vigor, potentially from low genetic diversity.

Lanky woolly milkweed seedlings growing many shoots – but hey, we were thrilled they were growing at all, so honestly we’re not complaining – just puzzled!

With winter coming on, and transitioning out of in vitro conditions being the most stressful part of tissue culture-based conservation methods, we will be planting these little weirdos into a well-drained potting mix and keeping them under grow lights in the lab throughout the winter. Some have developed great root systems, so we hope they’re ready to survive a little more independently.

Woolly milkweed roots forming in in vitro growing media.

Ok that’s great, you might be thinking, but how is this going to help us conserve woolly milkweed out in the real world?

This method may not be a silver bullet for the species; in fact, I highly doubt it. However, these are a few dozen plants growing that likely wouldn’t have been able to otherwise. A few dozen plants could make a world of difference down the road, especially in conjunction with other methods like cross pollination tests, seed bulking, and experimental reintroductions.

In conjunction with population surveys aimed at understanding responses to factors we can control like management and planting location, I believe lab-based methods like this can increase our capacity in the long run to produce more individuals for future restoration projects to stand against factors we can’t control. And what is species conservation if not seeking strength in numbers?

I believe this is the sweet spot where botanical gardens can fill a gap in conservation.

I know so many land managers who care about the rare species on their property, but simply do not have the time, money, resources, or training to prioritize the good of the individual species over the good of the whole. And, speaking as an academically trained scientist, academia simply doesn’t incentivize this type of research. Tiny sample sizes, uncontrollable factors like whether you’ll even be able to find the plants, species-specific methods that don’t generalize – these are nightmares for the classically trained scientist pursuing a research career.

Botanical gardens occupy the happy middle – we have research labs to deal with finicky or beleaguered species, and access to the horticulture community, which has been obsessing over how to grow difficult species for ages. We also don’t have publishing expectations nearly to the same degree that academic researchers do, and can afford to target “niche” journals and publish atypical, but still peer-reviewed research like propagation protocols, data papers, and natural history notes.

Yes, I know some gardens are already doing this, though in my (albeit somewhat green) opinion not nearly enough, and not nearly as many that should. In fact, in just over a year I’ve already heard one too many talk or seminar about rare species conservation that either mentioned land managers and long-term habitat management as an afterthought, or didn’t mention them at all.

So, I reached out to Bill and asked him if I could write a post for the GRN, introducing some of the work we are and will be doing in Nebraska, but also to post a request: land managers, what species are on your properties (or aren’t currently, but used to be, or are right nearby) that you would love to see in your restorations and habitats, but you can’t figure out how to grow them? How could people with access to botanical garden resources amplify the work you are already doing? Are there other thoughts sparked by this piece that stand out to you? If so, please reach out! I can also be contacted by email at k.hogan@omahabotanicalgardens.org.