By: Mike Saxton – Manager of Ecological Restoration and Land Stewardship at Shaw Nature Reserve – a division of the Missouri Botanical Garden – Gray Summit, MO

There are few acts more hopeful than planting prairie. We put so much effort and thought and love and care into the process and we hope for ecologically significant results. We want our efforts to translate into benefits for biodiversity and for the increased health of the land. And, perhaps a bit selfishly, we want to be proud of our good work, to show off our success, to reap the rewards of so much determination.

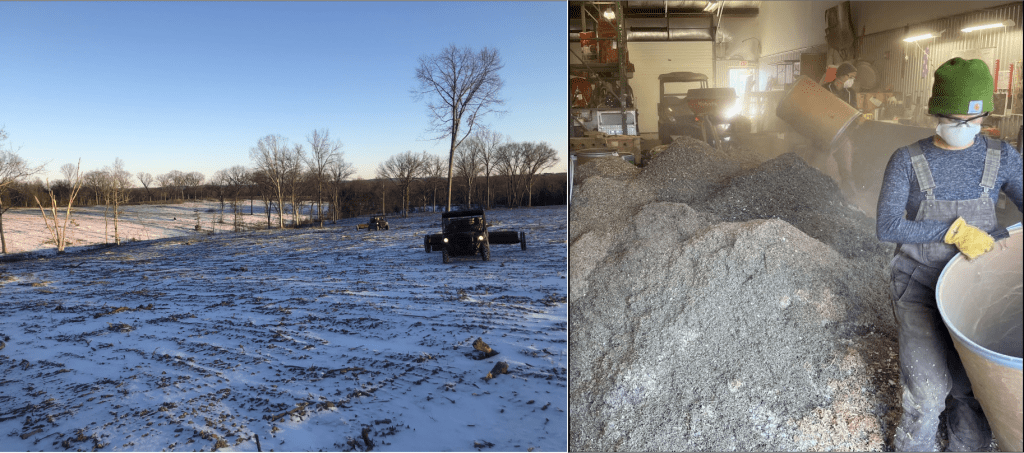

Left – frozen snowy ground for seed sowing of 40 acres on January 16th. Right – Restoration team mixing 1,000 pounds of hand collected, bulk milled seed.

Collecting seed, prepping the ground, sowing on a frosty winter morning…and then the hard part – the waiting. The agonizing wait. Once the seed is down, we want to chase off every bird we see feasting in the field. In the spring, we worry about getting enough rain. And sometimes about getting too much rain. Every day we’re out there expectantly watching for seedlings to emerge.

July 16 – Coeropsis tinctoria in all its glory.

Last January we sowed seed across 40 acres – mostly open fields with some open oak woods and some wet swales. This is part of a 120-acre land clearing/prairie & woodland restoration project.

• 244 total species in the mix

• All 40 acres received 1-pass of prairie seed

• ~2 acres received a wet swale mix

• ~8 acres received an open woods mix

• ~30 acres received a 2nd pass of prairie mix

• Roughly 25 pounds of bulk, milled, hand collected seed per acre

• 146 pounds of PLS purchased seed

• No big blue or Indian grass in the mix

• We are not high-mowing at any time during the growing season

• The 40-acres has been swept on foot for invasives by our crew. They report using a total of 1 gallon of herbicide per acre on Japanese stilt grass, Sericea lespedeza, and white sweet clover. More weeds than we’d like in a first year planting, of course. But extremely important to be on them from the beginning.

I walked the ground in the early summer hoping to spot seedlings. I didn’t like how much non-native brome I saw and I was impressed with the abundance of plain’s coreopsis (Coreopsis tinctoria) growing across the site (it was seeded but also was in the seed bank). I found many, many native plants but lots of the usual suspects too: fireweed (Erechtites hieraciifolius), mare’s tail (Erigeron canadensis), ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) and fox tail (Setaria pumila). We mostly do not worry about these distrubance driven annual Ag weeds.

Left – Bidens aristosa in background (wetter swale) with sprinkling of fox tail in foreground. Right – Partridge pea, mare’s tail and plain’s coreopsis – pretty typical for a first year planting.

Yesterday I walked the planting with a hopeful optimism. Generally, I’m happy with what I saw. I found flowering Liatris pycnostachya (prairie blazing star), Salvia azurea (blue sage), Agalinis tenuifolia (slender false foxglover), Physostegia virginiana (obedient plant), and multiple other species. Vegetatively, I found lots of Silphiums (compass & rosin), Baptisias, and Partheniums (quinine).

The most important piece of context – this ground was once forested, it was then cleared and converted to row-crop agriculture. In 1925, the Missouri Botanical Garden purchased the land, describing parts of it as “wasted farm ground”. It was then mowed for decades to be kept open. Then they planted blue grass and ran cattle on it. When mowing/grazing ceased (ca. 1960) it went through old field succession. Then we cleared the trees and are now asking the land to become a diverse prairie restoration. We need to be patient with the land and to attempt to understand what it wants to be and what it can be.

The Agony

A few patches of what I think is Bromus japonicus (Japenese brome). This area had been old-field succesional closed-canopy cedars and mesophytic hardwoods for decades…so it took us by surprise. There are native seedlings in and around the Brome, but not as many as we’d like.

Not extensive but some patches of a Digitaria that might persist. Mostly thin enough that native plants co-occur.

Large portions of the 40 acres have a spattering of fox tail. Some areas have nearly none while a few small areas have thickets.

The Ecstasy

Eryngium yuccifolium (Rattlesnake master), Monarda fistulosa (bee balm), Baptisia, Aesclepias, Lespedeza capitata (Round headed bush clover), Parthenium (quinine). These plants are growing around the remnants of a stump from the land clearing.

Obedient plant flowering with Baptisia, Salvia, Boltonia, Coreopsis and Aesclepias within 2ft.

Porcupine grass (hand-seeded in clusters across the unit – marked by pin flag), with yarrow, Liatris, and Parthenium.

We will be planting 40-acres of prairie over each of the following two winters. We will take the lessons learned from this first 40 and apply them to our subsequent efforts. This planting isn’t perfect but considering the context, we’re happy with these early results! And the planting will, hopefully, only get better with age and continued care.

Great post, Mike! I always tell people not to look closely at their restorations for the first couple years (other than to scan for serious invaders) but I never follow that advice myself. Instead, I crawl around on the ground, trying to convince myself itâll be ok, despite not seeing satisfactory numbers of prairie plants. It almost always works out well, eventually, but boy-o-boy, the wait is hard!

I have heard in the past that you should mow high at least once in the year after planting. Do you think that this is not necessary?

Thanks for the question, cdp9. Nachusa Grasslands typically plants 40 – 50 acres of prairie each year and it is not their practice to mow first year plantings. If there were patches of giant ragweed, those would likely get mowed, however. But they do not normally mow an entire planting, let alone mow it multiple times in a season. And their restorations are wildly diverse and successful.

I know folks here in Missouri who have stunning prairie plantings and they never mowed in year one.

There are a couple of reasons that we did not mow this prairie planting at Shaw Nature Reserve. 1) mowing 40 acres multiple times in a season is a big demand on staff time and that’s a challenge for us 2) we sowed a lot of seed, more than a thousand pounds and more than 200 species. We hedge our bets with volume of seed.

I assume that many proponents of mowing are typically planting as smaller acreage, thus mowing might not be such a time constraint. Also, I hypothesize that if you plant at the low end of species diversity and weight of seed that mowing becomes more essential. With the bare minimum of seed sown, every germinant is critical. So each little seedling needs every single advantage it can get. Because we plant heavy, maybe I’m less worried about establishment? That is just a guess!

Dr. Andrew Kaul – Restoration Scientist at Missouri Botanical Garden – and I had an email exchange the other day on this topic. Here was his response:

“Up in Iowa where I’ve mostly worked, first year mowing is frequently recommended and practiced. Most people trace that recommendation back to Carl Kurtz’s book from 2001 (A practical guide to prairie reconstruction) where he recommends starting as low as 3″ to hit the weeds early, and then moving the mower deck up for subsequent mowing throughout the first growing season. The Tallgrass Restoration Handbook (1997) also recommends mowing at 6 inches to prevent annual weeds from going to seed, or alternatively mowing regularly the first year above most prairie seedlings height. Similarly, The Tallgrass Prairie Center Guide to Prairie Restoration in the Upper Midwest (2010) recommends mowing to a height of 6″ whenever vegetation gets to 12-18″, which is roughly monthly May-Sept. The idea is that regular mowing prevents a single later mowing from laying down a heavy thatch. In my 100-site retrospective project, we found that establishment mowing (including sites that were mowed once or multiple times) increased site-level richness of similar plantings from ~20 to 24 species compared to no mowing.

My graduate advisor implemented a first-year mowing treatment in a follow-up study and found no difference between mowed and control plots. https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2664.14550 (figure 4).”

Thank you.

Do you have a list of species in your various seed mixes? 1,000 lbs of bulk milled seed is so impressive! I would love to know what all is in it!

Pingback: 2026 – GRN Annual Workshop – Shaw Nature Reserve | grassland restoration network